Practical Boat Owner February 1990

The nineteenth century amateur yachtsman T. T McMullen tells how he envied the fisherman their confidence and sureness of touch while he, after a disastrous first venture in which he almost lost the sight of one eye, was unable to get his three ton Leo underway without a feeling of brimstone in his stomach. His solution was to sail by day and night in all the worst weather until he attained a similar confidence. A few years later he was able to voyage from the Thames to Cornwall. Each newcomer to sailing faces the same problem although few tackle it in so determined a manner. For most of us learning is a far longer business. Unfortunately once you have become confident you face the second major problem of small boat sailing: Over-confidence! Most seasons Father Neptune claims the life of one or more experienced sailors who just got careless.

I was well aware of such dangers as I started my forty-second year as a small boat sailor but it didn’t prevent my clambering into my dinghy alongside Shoal Waters in a cavalier manner in February and capsizing it. Admittedly I was less than thirty feet from the shore on my mooring and the water was only three feet deep but I should have taken the hint!

I suppose that I could blame the glorious season of 1989 for lowering my guard. Nearly two and a half thousand miles of almost effortless cruising between Wells on the north Norfolk coast and Tonbridge deep in the heart of Kent, made the early September trip from Leigh to the Crouch via Havengore seem an easy leap. The lifting bridge is part of the M.o.D. weapons testing range and normally only open to small boats at weekends. By high water on Saturday the wind was piping up from the north and with one reef in the main and small staysail, we headed for the end of Southend pier through the fleets of racing dinghies and attendant rescue craft. It was going to be a fast trip until we came across a dismasted cat waving for help. I looked round for real help. Not a craft in sight! I threw them a rope and we towed them (under sail for I have no engine) into the shore near Chalkwell, taking the opportunity to lecture them on the futility of using elongated old tin cans for masts and advised them to stick to trees in future. Now it was going to be a race to get across the sands to the bridge before they dried.

Fatigue played its part. Lazy winds on Friday afternoon had left us on the sands east of the pierhead at dusk which meant a midnight move into the shore ready for shopping early Saturday morning and it had proved to be an uncomfortable berth with little sleep until she dried at first light.

Once round the pier we hauled our sheets and found we could point the Ness at Shoebury. Normally this is no advantage as a mile further on, the wartime anti midget submarine boom runs south across the flats for nearly a mile. Today this would mean a mile downwind and I decided to use the narrow gap in the fence close to the seawall near the Pigs bay yacht moorings. Looking back, I doubt if this in fact saved much time. Although it meant smooth water, the large barrack buildings stole much of the wind and the ebb tide inshore was surprisingly weak for the moored yachts in Pigs Bay near the fence were windrode.

Tearing along!

Worse still the gap was narrower than I remembered it with projecting ironwork to which the horizontal sections had once been fixed. As we raced through, the boat slowed, perhaps it was an eddy in the wind, perhaps the plate touched on a shallow spot. The result was inevitable. The brown curve of the mainsail hit the ironwork with a painful rending sound and the hull thumped to a stop alongside the barnacle crusted concrete post.

“Roll up the Jib” I shouted to Joy as I leaped onto the after deck and seized the iron protruding through the mainsail. At the second heave it went back through the mainsail and the boat leaped forward along the concrete posts.

“Harden up the topping lift” and I rushed to the mast to lower the mainsail. Then I tried to push off but she just went straight back.

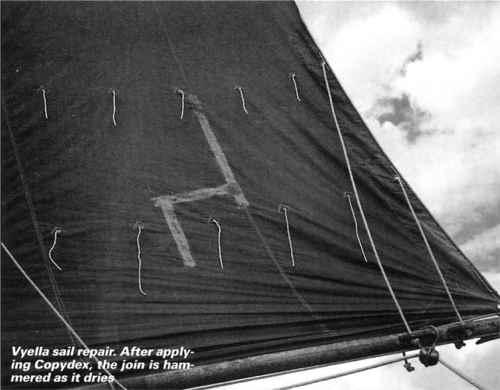

“Release the quant”. Joy unhooked the shock cord and I soon had the boat ten or twelve feet from the boom. The mainsail shot up and we were free. The tear was just below the second row of reef points, so once fifty yards clear, we pulled down the second reef and beat on northeast. With less sail, and other time lost, we failed to cross the watershed, the Broomway but by going over the side and towing the last few hundred yards until she grounded, we got very close; close enough I hoped to find the rising tide going toward the bridge rather than down the coast. As dusk fell I crouched on the cabintop repairing the sail by gluing strips of an old vyella sheet across the tears with Copydex and so to bed.

The returning tide reached us at 0015 hrs on Sunday morning. While brewing up, I watched the lights of Kent through the open stern of the cockpit tent. As she lifted they moved to my left and I knew that the tide would help me into the creek. Once she was well afloat I quanted further in with the swift tide. Two red lights came in from the northeast, small fishing boats, but we all stopped well short of the beacon. Shoal Waters is deepest forward, particularly with Joy still snug in her bunk, and the boat turned round to face the sea while still being carried towards the bridge by the tide, revealing her red port light to the other craft.

“Are you going out or coming in?” called a bewildered voiced in the dark.

“Reckon it needs another twenty minutes” called another. The wind was much easier now under a clear starry sky so it seemed a good chance to test the repairs made to the mainsail. To my delight they held and I tacked back and forth, grounding regularly, as the others edged into the deeper waters of Havengore creek. Suddenly they were away and racing towards the bridge to pass under before the tide rose too high for them to get through. In fact there is room galore under the new structure BUT the M.o.D. for reasons best known to them, have added a horizontal bar at the level of the old bridge. The fishing boats slowed and eased under before belting off into the night. I knew that there should be enough room for me with the mast down but this was no time to chance getting pinned against the bridge with a spring flood tide, a fate I saw befall a Wayfarer and an eighteen foot TEOD later that day. Thus I anchored halfway along the creek, well away from the foul bottom near the bridge, rigged the anchor light and got back into the sleeping bag well content to wait for the afternoon High Water.

Resisting temptation!

A small motor boat passed at 0430hrs indicating that the tide had fallen enough for him to get under the bridge but I resisted the temptation to try my luck. At 0600hrs it was light and I had a look out. The last of the ebb tide was going towards the Crouch. There was still enough water for me to lower and pass under the bridge but this was the coldest night for months and the warmth of my sleeping bag called me. At other times in other years it would not have worried me but after the heat of summer 1989 I have got soft. I should have watched the boat dry for the muddy bottom here is serrated by the swirling tides but I contented myself by checking that the cabin was laying out straight from the bows towards the fisherman anchor. My conscience told me that I should get out again to recheck but I didn’t.

Hours later in warm morning sunshine I put on my water boots and dropped over the side for a walk. Where was the anchor? A few steps to port showed the end of the stock peeping out from under the bilge. My heart sank as I plodded round to starboard and peered under the hull behind the mast to see one fluke pressed hard against the skin of the boat. With a home made paddle serving as a spade, I quickly dug down to the crown of the anchor and then the lower fluke. A firm push drove it down into the mud drawing the top fluke clear of the hull. I reached under the bilge to find a `little finger’, sized dimple. Back on board, we removed my bunk cushions and boards to reach the bilge. Any damage should be under the inside lead ballast but once that was lifted, none was visible. I have glued two narrow strips of wood to the inside of the hull to carry the ballast rather than let it sit directly on the half inch hot moulded skin of the hull. Could the fluke have met the hull directly under one of them?

I washed the outside of the hull near the damage with a sponge and left it to dry as long as possible. We heated the dry frying pan and held that under to help things along. Then I made good with Plastic Padding when the first signs of the returning tide appeared under the bridge.

Thus we returned safely to Heybridge duly chastened and determined to be more careful in future!