Practical Boat Owner No 330 June 1994

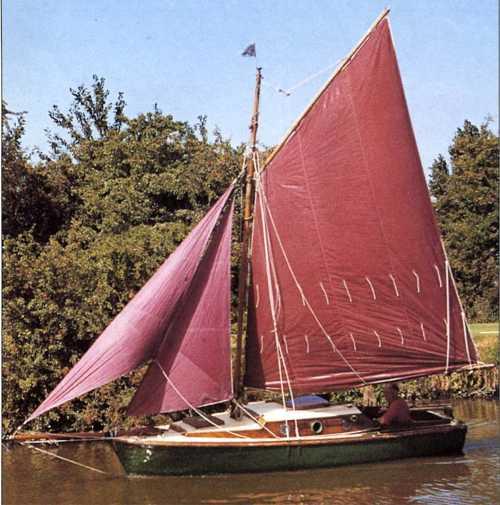

When I launched Shoal Waters in 1963 there was some surprise that I opted for gaff rig for the “leg o’mutton” (Bermudian) sail dominated the sailing scene. Gaffers were few and far between and many of those afloat were poor specimens of the breed. Topsails, of which Francis B Cooke wrote: ‘Men cursed them and swore they would have done with them; they went to their sailmakers and ordered larger ones’ were a rarity.

How times change

Thirty years later I no longer have to apologise for my old-fashioned rig. New gaffers are advertised in the yachting press and exhibited at Boat Shows. The OId Gaffers’ Race on the Blackwater each July is now a festival of the sailmaker’s art with over half the craft sporting topsails. With a start downwind it’s a sight that has to be seen to be believed for none of the usual restrictions on racing sails apply. If you can find somewhere to hang it, up it goes. A Dutchman who presented the prize some years ago summed it up when he said: ‘Neffer haff I seen boats mit so much sails!’ He hit the nail on the head. The great advantage of gaff rig is the large area of sail that you can carry downwind without resorting to balloon spinnakers or big boys. Cruising skippers don’t have the racing man’s obsession with performance to windward.

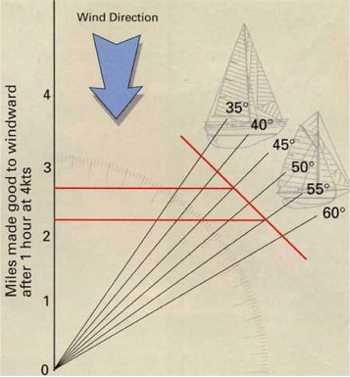

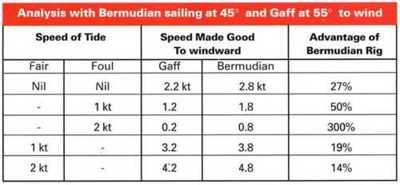

Look at it this way. The diagram on the next page shows a yacht close hauled on the port tack making four knots through the water. The courses show the progress of boats sailing 40-45-50 and 55 degrees off the wind, their position after one hour’s sailing at four knots and horizontal lines transferring these positions to the scale so you can read off speed made good to windward.

Exactly how high a boat points, including allowance for leeway, can be argued for ever but let’s assume that the bermudian cruiser points 45 degrees off the wind and makes good 2.8 knots while the gaffer sags 55 degrees off the wind and only makes good 2.2 knots. That’s a superiority of 27% for the bermudian boat. Apply one knot of foul tide to each vessel and the speeds made good over the bottom drop to 1.8 and 1.2 knots, a superiority of 50%. Increase the tide to two knots and the relative speeds become 0.8 and 0.2 knots, giving the bermudian boat a superiority of 300%.

But first, a confession. I’m a retired civil servant where everything has to be proved by statistics and a certain amount of, perhaps not cooking, but certainly slight warming up to get the right result is not unknown. Nevertheless what I’ve shown does actually happen in practice. A foul tide will sort out the boats with poor windward performance.

Facts from figures

No one likes being passed on the water; it can be a miserable business for the owner of the slower boat. Perhaps the worst cases occur on the Norfolk Broads when the bermudian boat can just fetch a reach of a winding, narrow river, round a bend to leeward, and scorch off with a beam wind while the gaffer has to make a tack at right angles to the river across a foul tide with all the dismay and delay that entails.

All is not gloom. Give the boats a fair tide of one knot and the speeds made good become 3.8 and 3.2 knots, only 19% better for the triangular sail and if the fair tide is two knots the speeds made good over the bottom become 4.8 and 4.2 knots just 14% better. This is still a substantial advantage and only tolerable if gaff rig will make up this deficiency to windward when sailing off the wind. A glance at the compass and the wind direction will show that for nearly three quarters of the time you spend sailing you will be off the wind. Thus, if we think of the case of the gaffer beating with a fair tide of one knot with a performance twenty per cent less than the bermudian boat, she must be at least ten per cent better on all other points of sailing. I’m pleased to inform you that she will be.

Homeward bound

The real bonus of gaff rig comes to the man who picks his weather and works his tides for the longer passages. Imagine running down the edge of the Foulness sands from the Crouch/ Blackwater/Colne to the Thames with a fair wind of Force 2/3 ie 7 knots. A fair tide of two knots decreases the wind on the sails to 5 knots and if you have enough canvas to make 3 knots through the water the wind hits the sails at just 2 knots. Beat back six hours later with the tide now against the wind.

The seven knot wind is now 9 knots because of the tide and if you make good 2 knots to windward the effective wind on the sails is 9 knots. Think of those times when you’ve been sailing down wind in shirtsleeves and turn to beat home.

It’s a chill wind

Suddenly it feels colder and you reach for a sweater. The temperature hasn’t changed but the wind chill factor has because of the increase in the apparent wind. Thus on average the cruising man will find more wind when beating than when running or reaching.

A word of warning here. There’s nothing magic about having a bit of wood at the top of the mainsail. Gaff rig is purely and simply a way of hoisting more sail on a given boat. It becomes particularly important as the man who goes to sea for fun tends to sail most in light weather and stop home in hard winds. Some of the modern ‘Boat Show’ gaffers look to me like bermudian boats with a slit across the mainsail to take the gaff. Even the topsail doesn’t extend beyond the top of the mast. You cannot have a standing backstay with gaff rig so the boom may as well extend well over the sternpost to give a really large sail area. Several of our old gaffers have booms longer than their waterline length. A yard will carry the topsail well above the mast head to give more sail area where the wind blows strongest. The gaffer with a short boom may suit the proud owner but won’t give the performance off the wind to make up the loss of performance to windward.

Few people have experience of both types of rig on the same boat, but I met one last summer. He lost his gaff rig together with topsail over the bows in the Yare Navigation race and decided to take the opportunity to go bermudian. In spite of cutting a hundred square feet from the mainsail, he was surprised to find that he had to add another three and a half hundredweight of ballast to the keel to restore her original stiffness, which seems to answer the criticism that gaff rig has too much weight aloft.

All in the sag

I suspect that the explanation has much to do with the tendency of the gaff to sag to leeward. This is normally quoted as a deficiency of the rig; usually by people who’ve never used it. In practise, this is a major safety factor for, as the boat heels to a squall, the sagging gaff lets much of the force of the wind escape harmlessly over the top. In the same situation a bermudian rigged craft with a kicking strap holding the mainsail flat, can only relieve the pressure of the wind by heeling over even further.

The point I’ve tried so laboriously to make is that if you spend a lot of time beating over the tide, go bermudian. If you can so order your affairs as to normally work a fair tide to windward, gaff rig will serve you better. Of course the racing man wants windward performance because he must sail the course set by the race officer. This will often include a beat over the tide.

I recall enjoying a drink aboard a certain royal yacht some years ago during a well known early August Regatta and listening to the owner’s husband, a man know for his forthright opinions, expressing the view after a day in which few boats crossed the finishing line (himself included) that the race organizers never consulted either a tide table or a weather forecast. Things get worse as you go down the racing ladder.

On the other hand, the cruising man will take a fair tide as naturally as he selects the up or down escalator at the underground station depending on which direction he wants to take. So it’s gaff rig for cruising every time…