Yatching world May 1973

In 1705 an Act of Parliament established the navigation on the lovely river Stour between the counties of Essex and Suffolk from Sudbury to the tidal estuary that runs into the sea at Harwich. Now an Act of Parliament has extinguished that navigation for all but canoes and similar craft for they have built a barrage across the river below Cattawade bridge to conserve fresh water for drinking purposes. This prevents craft from the sea entering even the last navigable stretch as far as Flatford mill. I keep a small gaff cruiser at Heybridge on the river Blackwater and over August bank holiday 1969 I decided to try to get round to Flatford once more.

A northerly airstream settled over the country at the end of August. This was fine for the trip home but meant a difficult trip north under sail. If you are not round the Naze by the time the tide starts flooding south you will not get round for a long, long time with a head wind. The derelict lock at Brantham between Cattawade bridge and Flatford can only be negotiated when the tide outside is higher than the water above the gates and thus I had to get through soon after midday on Saturday. Once round the Naze and into Harwich, the morning flood tide would help me on my way in great style for the moon was just after full and tides would run hard and rise high. A quick trip to Harwich was essential. In small boat cruising it is a case of ‘If at first you don’t succeed; give up’. A north easterly slant would mean beating all the way from Clacton pier while a north westerly slant would enable me to pass Walton before having to beat.

My craft Shoal Waters dries on her mooring for six hours each tide. High water was at 0323 on Saturday morning. I took my gear out over the mud. tied my boots alongside to be washed when the tide returned and got a few hours sleep. The 0200 forecast gave N W Force 4 to 5 and the trip was on. As I washed my boots in the soft black water, red navigation lights were coming down Colliers Reach from Maldon, three barges underway. What better companions could one ask for such a nostalgic voyage? By 0245 I was underway with a large jib but close reefed mainsail. 1 cut behind Osea Island and got ahead of the barges but in the occasional glimpses of moonlight through the overcast sky, off Bradwell, I could see that at least one was still coming out of the river and at first light off the Colne bar, realised that all three were bound north with me. Today of course these craft are yachts but mostly retain their basic appearance and keep afloat financially by taking enthusiasts out for weekends or full week cruises. Long may their towering red spritsails decorate the Essex coastline. Thems as wants it can dote on their modern art and ornaments; eighty feet of tarred hull and three thousand square feet of weathered canvas against a blue sky is more to my artistic appetite.

Outside Harwich I met the barge Westmoreland bound south but the flood tide that was helping her, was holding me back and it was with a sigh of relief that I crept against the flood stream into Harwich. The three barges had a hard beat before they could get into Harwich but of course they had less ambitious plans once they got there. After passing the busy harbour installations at Felixstowe, Harwich, and Parkstone Quay I was sailing in quieter waters. In one spot the cattle had wandered down the beach to wade hock deep in the water and I sailed over to pass the time of day with them. It would have been nice to moor at Mistley alongside the stately mills and Maltings for it was from here that the lighters were loaded or unloaded from Sudbury and other places along the Stour navigation, but with an onshore wind it was out of the question and in fact I beached at Manningtree and walked ashore over the sailing club hard to do a little shopping.

Just before noon I left and beat up to the rail bridge where I anchored to lower my mast. From now on I depended on the flow of the tide for progress with a bit of help and guidance from a ten foot bamboo pole. The span nearest the Essex shore has extra clearance and I took this as a matter of principle although for a small boat such as mine there was room all the way along. The lovely old bridge at Cattawade is more difficult to negotiate without touching. Since I first passed under in 1965 the underside of the main arch has been rendered over, obscuring the marks and grazes made by passing craft over the last two centuries but I saw that someone had scratched the new cementwork. By the time I drifted the further half mile to the lock gates the salt water was within two feet of the fresh water above the gates. Brantham mill had vanished since my first visit and the mill run is now filled in and built over. I suppose it is some small compensation that they make yacht rigging, including probably, the rigging of my own boat.

Brantham lock, together with the next three upstream, was rebuilt completely in 1934, but it is a sad sight today. The top gates are permanently open. The lower two open when the tide rises and allow tidal conditions as far as Flatford. When the tide begins to ebb they close and hold back a reasonable level of water. The real snag is that a girder bridge has been built over the lock giving headroom as the gates swing open of about 40 inches, which of course rapidly diminishes as the tide rises. Lowering the mast in the normal way is no use here. I have to remove the sliding cabin hatch and get the gear right down snug. This gives about three inches to spare. Shoal Waters waited patiently with her short bowsprit against the apex of the gates as I stood on the cross member of the gate while the tide rose the last half inch so that I could lean over and pull the gate towards the girder of the bridge. I had to get them open just that few seconds early to enable the boat to pass under in still water before the tide started rushing through like a millrace.

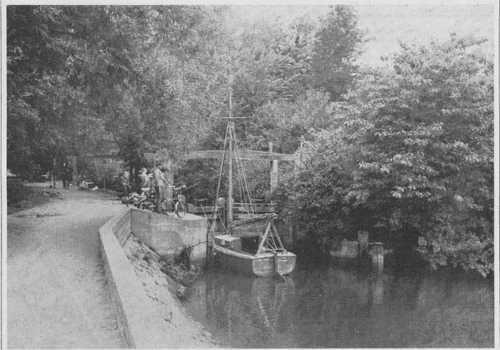

Then it was just a matter of getting up the gear and sailing up among the reedbeds to Flatford. There are trees for the last hundred yards. At 1420 I anchored in the millpool, had some tea and a snack and got a few hours sleep. There was a fine shoal of grey mullet playing round the boat when I woke and when I moved over to the lock gates in order to be able to get ashore (hospitality is not the strong suite of the outdoor studies centre here in the mill house) large carp could be seen nosing round the gates through which a little fresh water flowed. I suspect that they may have been discomforted by the salt water driven up by the high tide for there were jellyfish about. Some youngsters were having a fine time catching bream in the lock itself. For the night I moved out into the middle of the pool again to avoid being disturbed by the rise and fall of the night tide and was lulled to sleep by the song of the water pouring over the weir, broken only by occasional complaints from a duck somewhere out in the night.

On Sunday morning voices told me that anglers had made an early start. I lifted the forehatch and looked out to give them a cheery ‘Good morning’ and all I got were hostile stares and heavy weights dropped very near my hull. Sensing that 1 was spoiling their sport, I paddled slowly over to the weir to put a line round a post ashore so that the boat would lay clear of the dangerous looking timber and concrete banks, ‘You cannot moor there. It is private property!’ screamed a young lady from the millhouse. I thanked her for her information and stayed put, but the magic of the morning in this idyllic location was broken. The bitter hatred between the fishermen, the people at the outdoor studies centre and the tourists bewilders me. Surroundings such as these fill me with goodwill to every living thing. Even the ducks and swans here get on together better than I have ever seen them anywhere else. Homo Sapiens hates on regardless.

There was some light rain during the morning but the sun came out as I prepared to leave at 1045. The first few hundred yards were delightfully slow as the church bells rang out across the fields. The water was lower now than when I came up and on the windward stretches I poled her along for it was too shallow at the edges to beat. The wind had gone north easterly. I was early at Brantham Lock and tried to sail up the channel that once led to the mill but it was too shallow to get far. I lowered down the gear in the lock, pushed the boat under the bridge and sat on the lockside as the tide rose steadily. It was a pleasant spot indeed, and I was sad to think this navigation is to be closed for all time. Getting out against the flood is even more awkward than the trip into the lock, but all went smoothly and I had lunch in the lee of the reedbanks after getting the gear up. Then I sailed up to Cattawade and back a couple of times as the flood tide finished. Down gear again, under two bridges and away down to Harwich as the sun vanished behind cold purple clouds for the rest of the day. That night I lay on the mud opposite Pin Mill on the Orwell.

At 0600 I was off with the ebb. The forecast at 0640 came before I left Harwich and gave NE Force 3 to 4. Wind and tide were in my favour and I enjoyed a rollicking trip out round the Cork sand to the Roughs Tower before turning south for a hectic run home. Roy Bates’ (who was then selfstyled President of the independent state of Sealand) men on the tower may be pirates but they at least gave me a cheery wave as I passed. At three-thirty on Monday afternoon Shoal Waters lay on her mooring at Heybridge again having said farewell to Flatford.